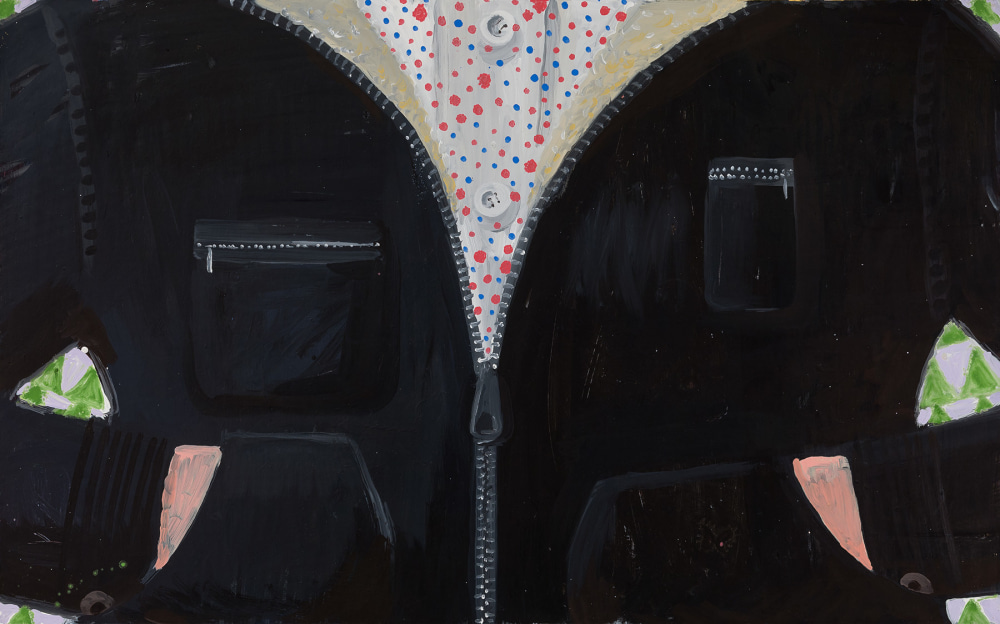

Elena Sisto, Black Jacket, 2013-2014, Oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. (BP#ES-7599)

In the late 1980s, Elena Sisto made a series of paintings of empty picture frames, directing attention to the conventional moldings and materials that normally surround an image. Emphasizing the artificiality of the convention by her careful and precise details, she ironically underlined the frame’s profound historic importance as a resource for pictorial invention, one she continues to mine in her current show, Afternoons. As she now fills the frame with close-ups of her body and studio, Sisto still seeks meaning at the margins of perception, depicting what is displaced or fragmented.

Sisto’s first show at Bookstein in 2013 featured paintings of a young woman artist in her studio; the irony of the series centered on how the efforts of this presumably conscientious art student were undercut by the off-kilter framing and unconventional composition that Sisto imposed on her—Sisto herself steeped in tradition but harboring an urge to push boundaries. In the current work, this narrative fiction has collapsed: the works are rooted in the perceptions of the artist herself, in close-ups of her torso and hands, and of items in the studio that serve as her proxies. But psychological tensions persist, arising from the shared predicament of both artist and spectator: that of being confined within a body and a point of view.

Sisto’s frontal close-ups of women in shirts and jackets have become something of a signature. Focusing on the designs of clothes and accessories to create a tightly composed façade, the flattened symmetry of Black Jacket (2013 – 14), tight as a drum, could be compared to one of Gary Stephan’s recent abstractions, where overlapping shapes both conceal and reveal. Sisto zooms in on the cues we note in assessing a person and her story, but also the sort of things we observe in moments of distraction, like the teeth on a zipper. In a recent interview, Sisto spoke of her interest in Freud, and her images can be read as puzzles or games of hide and seek, haunted by what’s unseen or unsaid. Drips of paint and the casual mess of the studio assume symptomatic significance; in Salad (2014 – 15), food enters the pictorial mix, instinctual pleasure conveyed with an elaborate play of reflections across the internal frame of a mirror.

There’s a loosening of formal constraint in the recent work, as Sisto experiments with a new, more fluid medium, combining water and oil, and with a new alter ego—her small dog, Busby, who appears, like the artist herself, in fragmentary glimpses. He submits to her embrace in the wild and intimate Busby II (2013 – 15), where Sisto’s grasp on the dog disrupts the façade of her body with splayed, furry legs. Sisto’s face appears in one off-hand, fugitive self-portrait, Afternoon II (2014 – 15), as though caught accidentally on camera, almost dematerialized in a wash of gray hair and summarily indicated features. As though to compensate, she devotes great care to the marginal details—the beveled frame of the mirror, which repeats her features, slightly displaced; and the decorative details of the mirror’s frame. The casual accuracy of these renderings attests to Sisto’s ability to achieve the effect of realism, even in broadly simplified depictions. Her technique ranges from the delicate rendering of shadows around buttons to the massive materiality of Boot (2013 – 15), and we admire how, with the same sort of pink, she distinguishes a finger from a fingernail in Splurt (2013 – 15).

Sisto is indebted to Matisse, another artist interested in patterns and couture (his Romanian Blouse (1940) comes to mind), but patterns and cropping also link her works to the intimate interiors of Bonnard and Vuillard. Matisse himself was inspired by Vuillard early on, fascinated by the way his figures merge with patterned wallpaper, allowing the viewer’s attention to roam and suspend habitual focus. Sisto cultivates such suspension when she draws back from her trademark close-up view, as with the randomly organized objects of Couch (2013 – 15). In Rainbows for L (2013 – 15), there’s a hypnotic effect to the dangling crystal, its disembodied spectra floating over loosely rendered draperies. (Busby’s truncated figure also recalls Bonnard’s casual depictions of dogs.)

These more open, informal spaces seem new to Sisto’s work; their vaguely defined fields offer the potential for new surprises. In Busby’s Burger (2013 – 15) she returns to the conceit of making paintings of paintings, while teasingly offering a treat to her alter ego. But the burger hovers in a mysteriously unframed space, ambiguously disconnected from the stretched canvases around it—an object of desire made “real” but inaccessible—an allegory, and argument, for painting itself.